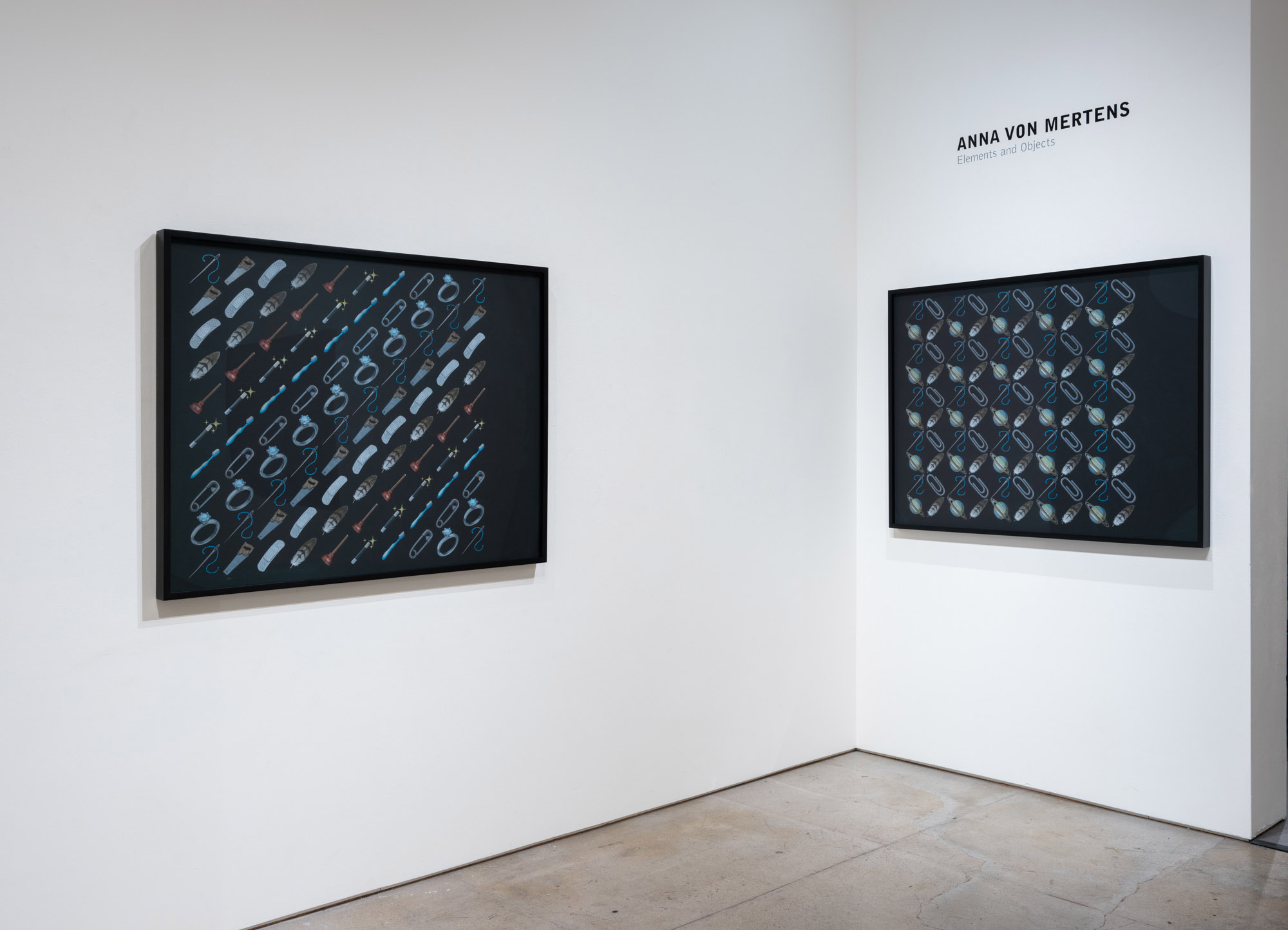

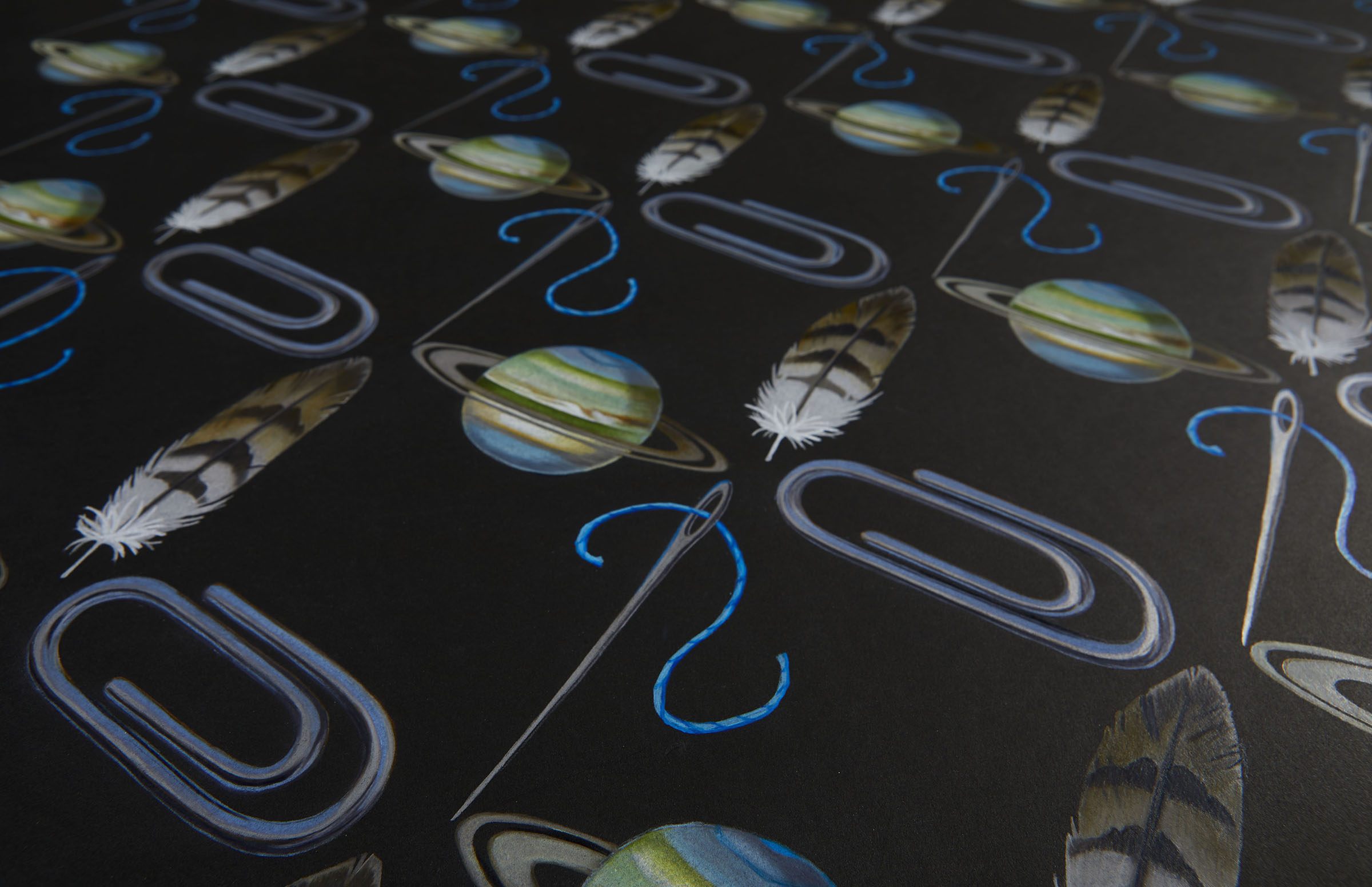

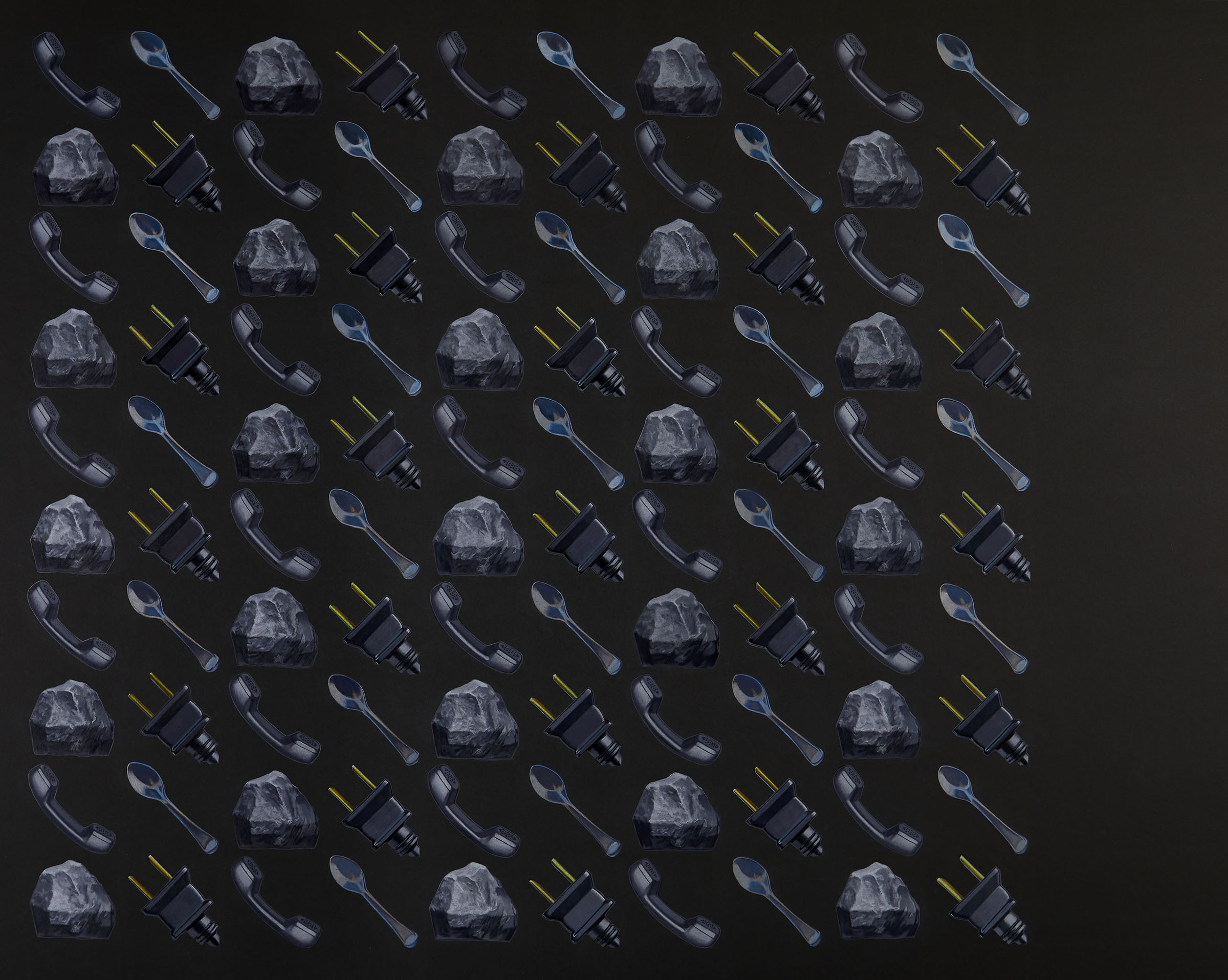

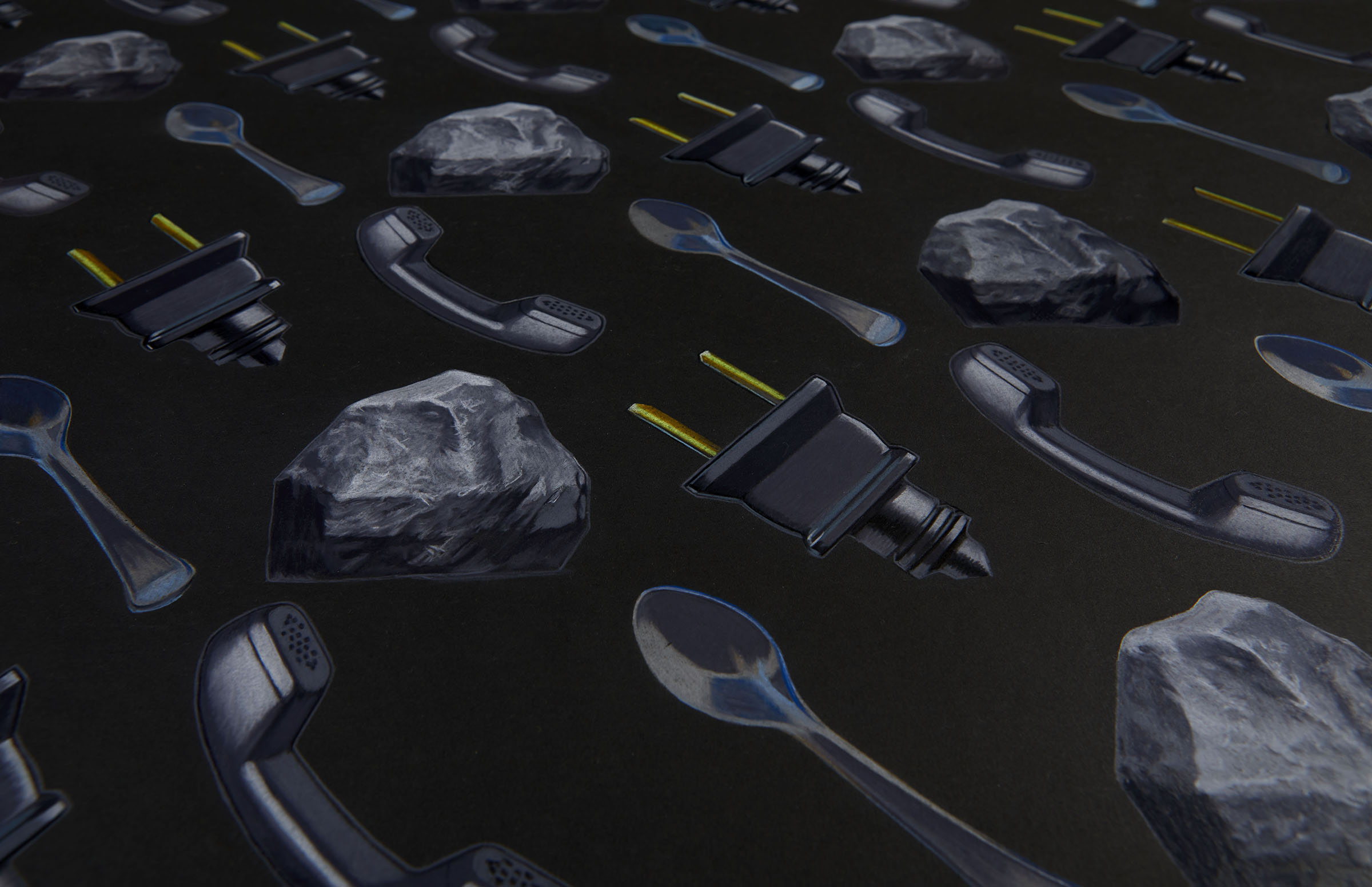

Each of the three drawings in this series uses pattern to animate the symbols that populate our phones. In one drawing, items of mending, tending, cutting, and repairing—and a little magic—repeat in a diagonal cascade, their replication a simultaneous assertion of presence and meaninglessness. In another, the slanted shapes of four emojis are arranged and repeated to evoke the traditional Tumbling Blocks quilt pattern. In a third drawing, the sheen on plastic and metallic surfaces pulls shapes from the black background; their materiality speaks to the elemental nature of all things: minerals that constitute rocks, copper that carries current, spoons that deliver nutrients to our stomachs, phone receivers that bring sound waves to our ear.

We humans tend to think that we, not things, possess agency, and that there lacks a certain realness to what we see on our phones. Giving these objects hours of attention is a reminder that they are an actual presence in our lives. Our phones are as much a part of this world as anything else. We share the same ecosystem.

These drawings take root in the objects category of emojis. Theorist Bill Brown’s description of Thing One and Thing Two might provide the best description: they are “baldly encountered” but “not quite apprehended.” These emojis meet the standards of being an object—indeed their functions and usefulness had to be articulated to make it through the Unicode emoji approval process. But once on our phones, these symbols quickly start to slip down Heidegger’s slope from being an object toward a thing. Even as we assert control over these objects and subjectively redefine their functions with the press of our thumbs, the thingness in them offers resistance. When Jane Bennett writes of thing-power in her tour de force book Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, she “seeks to acknowledge that which refuses to dissolve completely into the milieu of human knowledge.” By hand rendering these symbols, perhaps a bit of Jane Bennett’s “vitality intrinsic to materiality” comes even more alive. My engagement with these supposedly disenchanted objects discloses their own enchanting quality, the possibility of which Bennett discusses in her earlier work The Enchantment of Modern Life. Something is shaken loose and awakened, a kind of tender delight. We pull these objects towards us, but the stupid silliness of emojis—perhaps their greatest strength—persists, and they slip away once more.