Nature and Other Relationships

Emojis and drawings seem worlds apart in tone and technique. Emojis are cartoonish stand-ins for feeling, fired off with a flash of the thumbs. Drawings are intimate, personal, pulling you in. My emoji drawings destabilize this polarity. They borrow equally from both sides: at once silly and earnest, superficial and specific, contrived and exquisite. From a distance my drawings click into place, almost as slick as the surface of our screens. Walk closer and the choices of the hand become evident; no repeated mark is the same. Emojis might be generic and collective, yet each time we hit send we make their language our own. What appear as offhand gestures, with close looking become heartfelt missives. Despite their immediacy, emojis have a latency that my drawings resolve.

Nature and Other Relationships examines how our use of emojis illuminates relationships—relationships between mother and child or longtime friends, the relationship between surface and meaning, our relationship to our devices, our relationship with what we define as “real.”

In the drawing Nature I depict all of the emojis in the category Nature, which can be read as a one-liner about our paltry relationship with the natural world in our digital age. But this group of emojis is also evidence of how, in our rituals and traditions, elements of nature are original sources for meaning: the evergreen tree as a symbol of resilience during the darkest time of the year, or the bamboo shoot welcoming growth and happiness in the Japanese New Year. The line between ourselves and nature can be a useful one, preserving wildlife and wild spaces. But that situates us outside of nature. We have constructed that boundary. Nature occurs around us, within us, and by us. Our phones are part of this ecosystem.

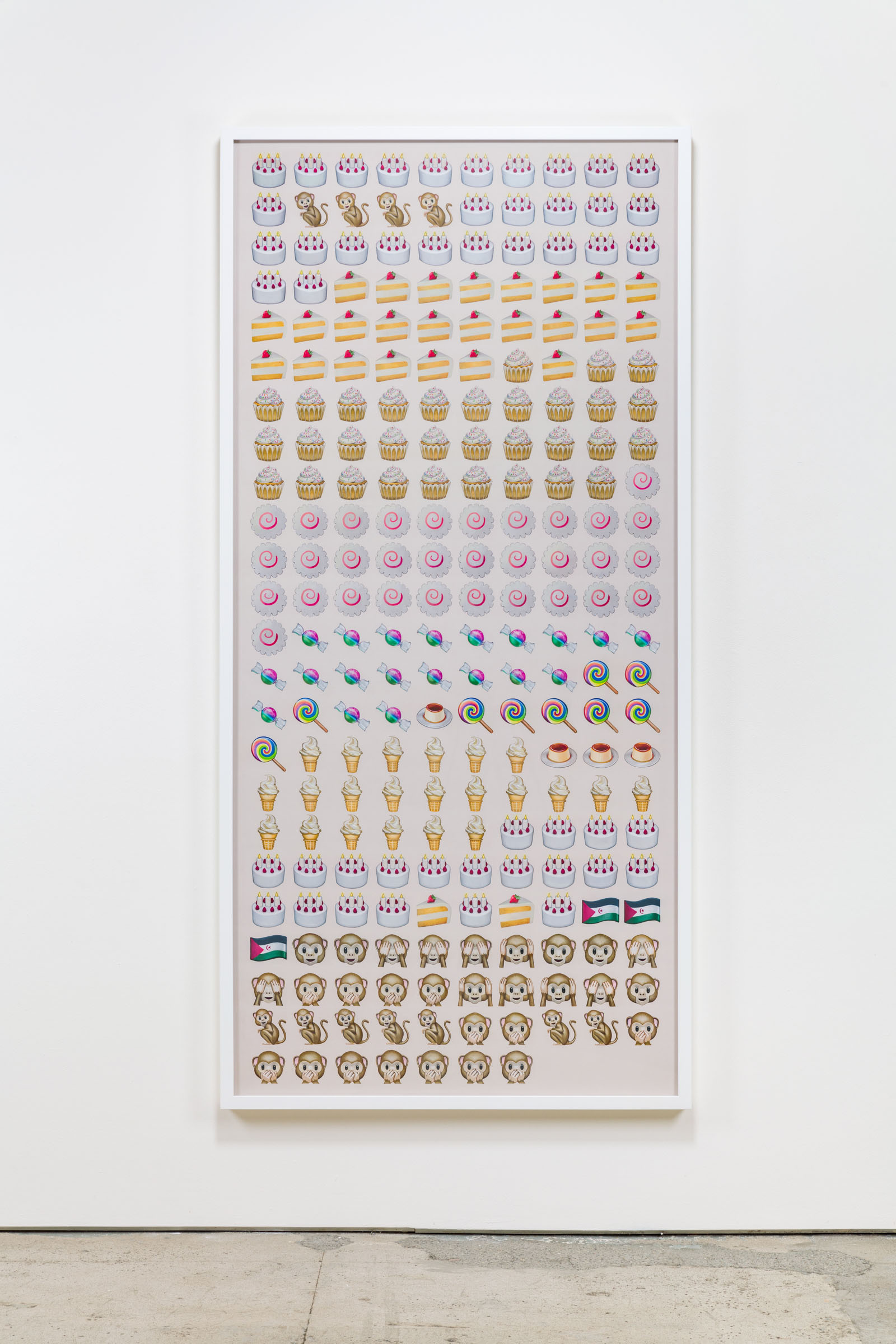

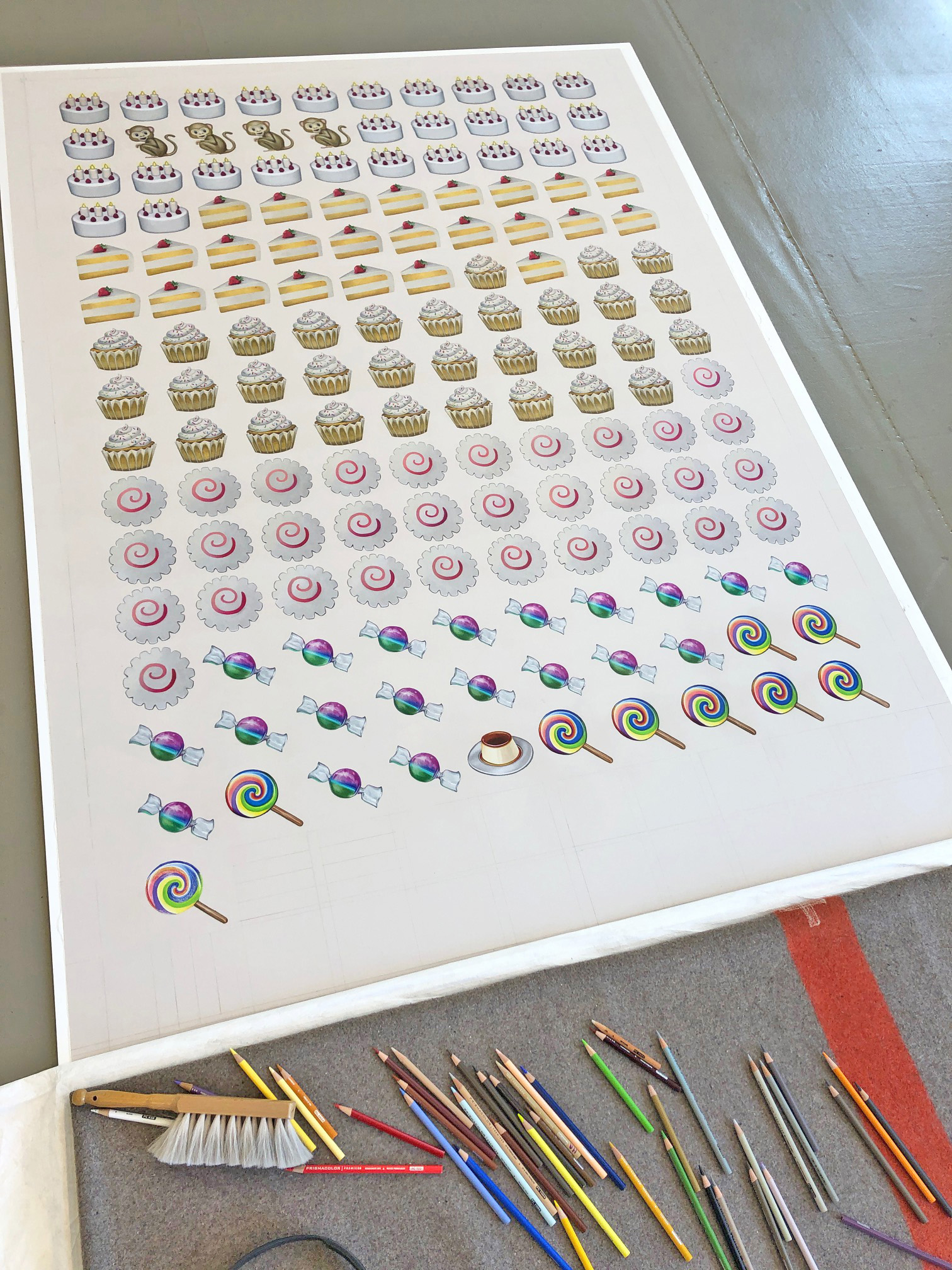

The largest drawing in the exhibition, Whoh (J.J.’s text to her mom from her father’s phone, Sept 4, 2019), is based on a text sent by a five-year-old to her mom about her love of sugar. Translated into an eight-foot tall drawing, the drawing becomes an operatic score of desire, conviction, addiction, and excess. The monkey is a protagonist in this narrative, introducing mischief, morality, and empathy. After row upon row of sugary treats, three Western Sahara flags are a surprising inclusion, especially considering how far you have to scroll to get to flag emojis from cupcakes. (When asked to clarify, J.J. said her stuffed animal did it.) Well, everything is political. The last row of speak-no-evil monkeys I see as vacillating between horrified surprise, complicit silence, and suppressed giggles. It is a musical composition replete with held notes and motifs, a reprise of the monkeys after an interlude of flan and rainbow lollipops. Seen as a literary text, my drawing becomes a close reading.

In the process of belabored drawing, repetition becomes its own subject matter—not just the wow factor of the stamina required (although let’s admit 237 emojis in one drawing is a LOT), but repetition as its own form of relationship. For what else are our relationships but repeated actions: how you greet each other in the morning as your child clumps down the stairs, how the dishes are cleared from the table after dinner. We must navigate this space of joy and pleasure, boredom and sameness, nuance and complexity.

I make each drawing the way each original text was composed: emoji by emoji, row by row. Forecasting into the future doesn’t help—I might know I have 113 more emojis to draw, but that’s not a very useful thing to dwell on; the past is not a visual reference point—I literally cover it up with a sheet of paper to protect what I have already drawn. Which leaves me suspended in the present. Which, of course, is where we always are, despite our routines. The construction of this drawing is a continuous reengagement with that fact.

For each symbol, I start with an enlarged version of the emoji on my computer screen, sketching what I see in graphite. As soon as I feel like I’ve gotten the proportions right, somewhat absurdly I erase my marks until just a ghost remains. Otherwise the colored pencils would get smudged by the lead.

I then build the color in layers. The wax binder keeps the pigment suspended, allowing me to blend new colors into ones I’ve already put down. It feels like mixing paint right upon the paper’s surface. Some colors are very forgiving, letting me push the color around until I’ve got it right. Other pencils, like the cursed greens, are harder, truly: they contain less wax and therefore aren’t as friendly to work with.

The complexity of color astounds me: lemon yellow, burnt ochre, chartreuse, bronze, and goldenrod combine to produce the flame of a birthday candle. My colors are not made by dragging a cursor across a gradient on a screen. The chimera of a monkey’s shimmery fur is a continual mystery.

The first time I draw an emoji I proceed at a snail’s pace; all of it is new. The thirtieth time I’m as much drawing my memory of the drawing as the object itself. Sometimes I remind myself to return to the original source and make new decisions—today’s decisions—based on what I see. Other times I let it be a memory, a path worn familiar.

If I screw up, there’s no erasing. Whatever happens becomes the drawing.

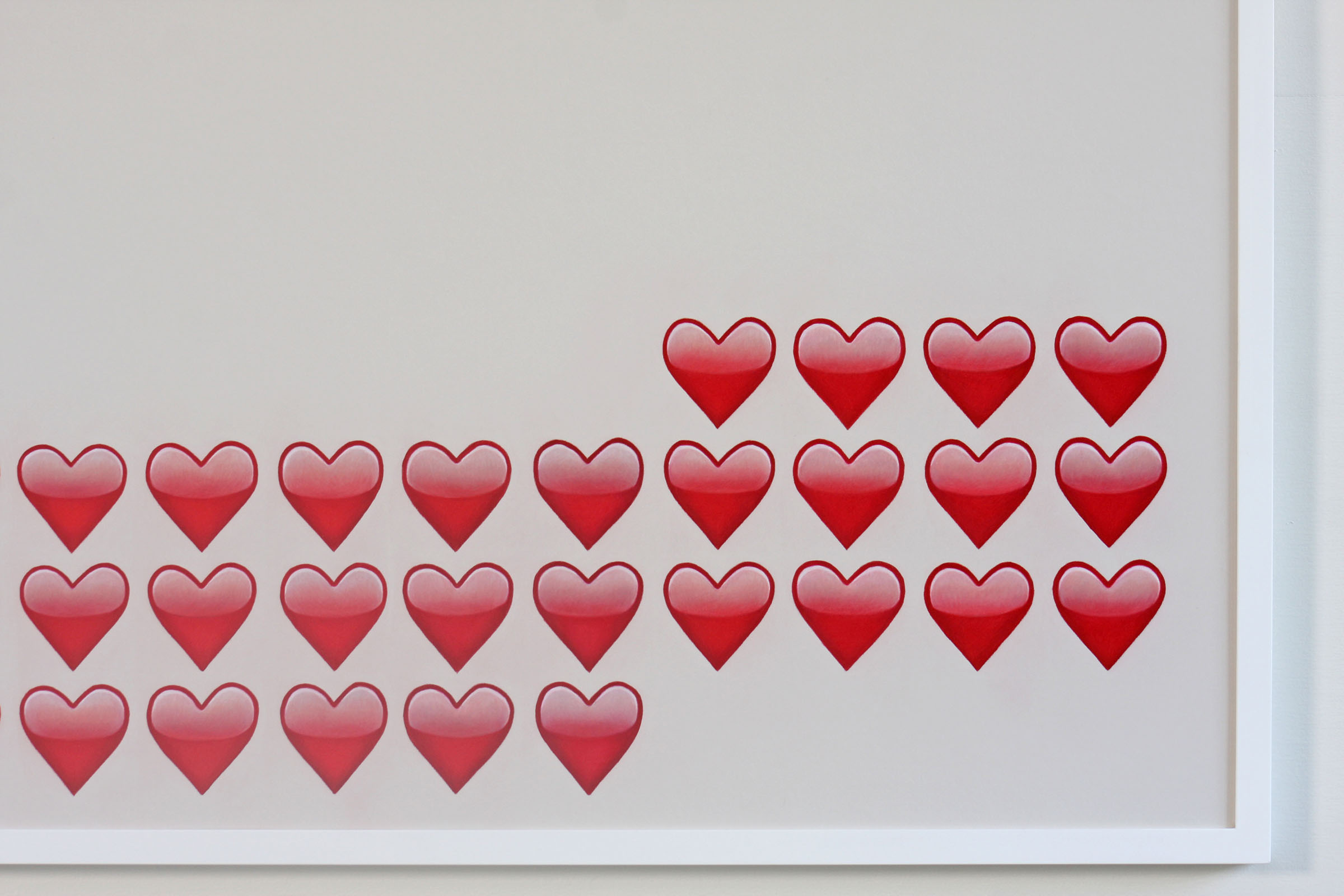

For another work in the exhibition, Every text from Joy that includes an emoji (Jun 18, 2016), I keep the proportions of my friend’s original text the same, but substitute blank paper in place of words, drawing only the thirty red hearts that conclude her message. The drawing uses the language of minimalism, yet one steeped in intimacy. It becomes literally heart-centered, a meditation on the small and large gestures that build a friendship.

Six crystal ball drawings, part of a larger series, are included in the exhibition. Choosing the crystal ball as a symbol implies a search for meaning, seeking insight into an uncertain future. It also investigates the present. Drawing the same object over and over again asks the question: Am I paying attention? In my studio practice, I interspersed my repeated drawing of the crystal ball emoji among other projects. Each time I sat at my desk to begin a new crystal ball drawing, I was surprised how excited I was. It was not an exercise in tedium; it was one of discovery.

Looking closely is its own reward. Our phones are magical, miraculous—and, accordingly, illusory. When absorbing information from my phone, I find it doesn’t settle in my body; it does not become an experience. Just a stone skipping across the surface. Yet these cursory, repeated touchpoints shape us—shape our physical posture, our interactions with others, the structure of our attention. While glances at our phones may be fun and fleeting, the effects are considerable and durable. In taking up a pencil, I take my own action. I found my way into a world that is nuanced and absorbing. The information is incorporated; it becomes corporeal. The experience lands.

The spaces of the virtual and the real are not isolated; we travel a continuous circuit between these two poles. A friend’s young daughter was newly allowed to borrow her mom’s phone so she could text her friends. Instead the girl walked down the street and around the corner to send her parents a cascade of emojis. Emojis might live in a world that is both real and not real, but they steer us toward each other. A child’s first texts can appear to be a visual free-for-all. But they say: life can be fun, and we like each other. In returning to the body, in returning to the material, my drawings by hand remind us of the wondrous, revealing, and evolving world we live in, all parts of it.