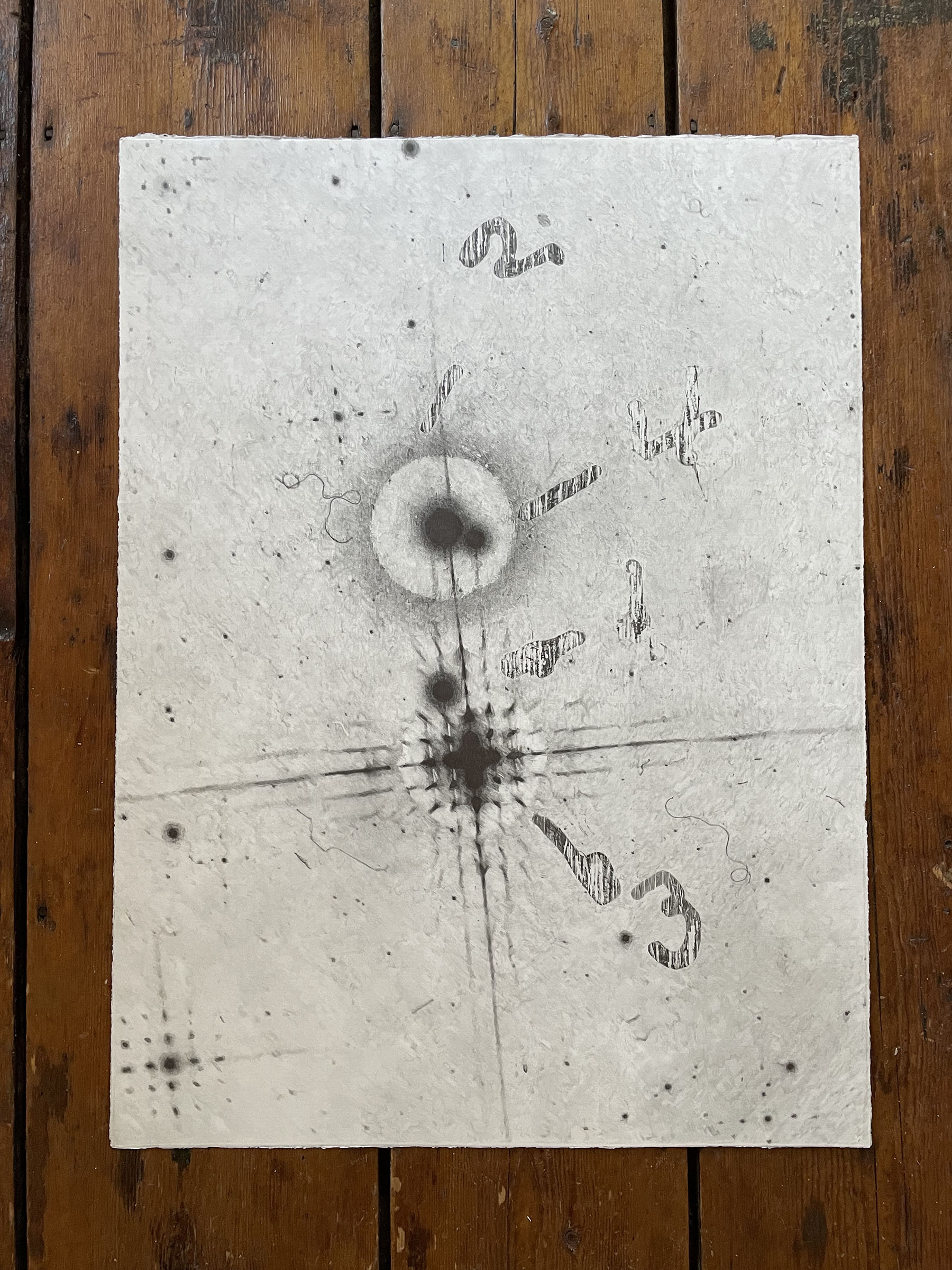

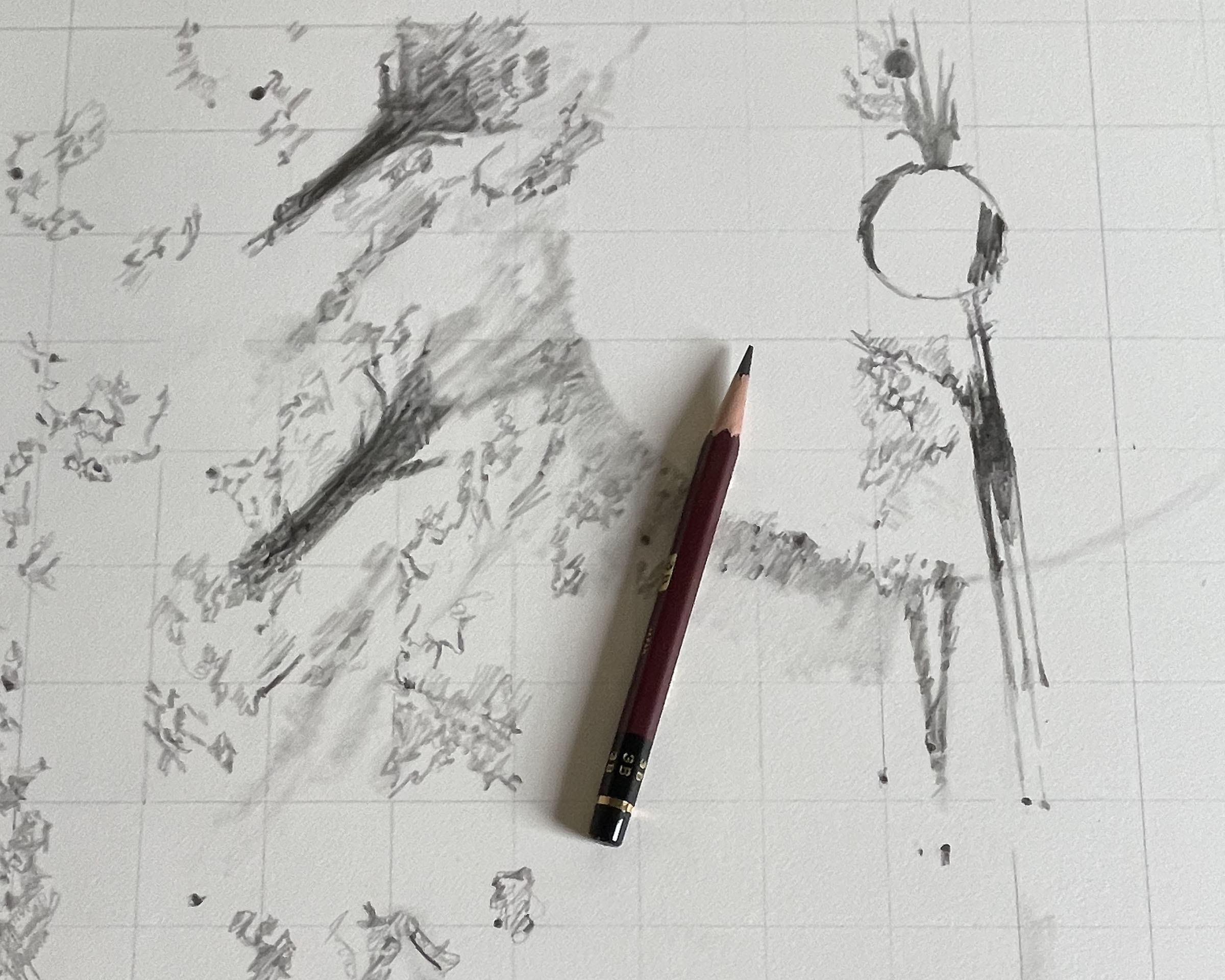

I created the drawing series Polaris Portraits in conjunction with writing my book Attention Is Discovery: The Life and Legacy of Astronomer Henrietta Leavitt (MIT Press 2024). The book celebrates Henrietta Leavitt’s foundational 1912 discovery of the period-luminosity relation in Cepheid variables; this natural law that Leavitt established enabled astronomers to measure the distance to faraway stars for the first time, launching modern cosmology. But after this groundbreaking work while employed at the Harvard College Observatory, Leavitt was assigned the task of standardizing photographic magnitudes—determining the brightness of stars as recorded by telescopes on glass plates—which was a seeming demotion from her earlier role. Yet this work was essential in order to make any investigative progress toward understanding the pinpoints of light in the sky about which so little was known at the time. Leavitt’s germinal discovery made it possible to conceptualize the cosmos. Her work standardizing magnitudes was also significant and examining this “ordinary” work reveals how extraordinary it actually was.

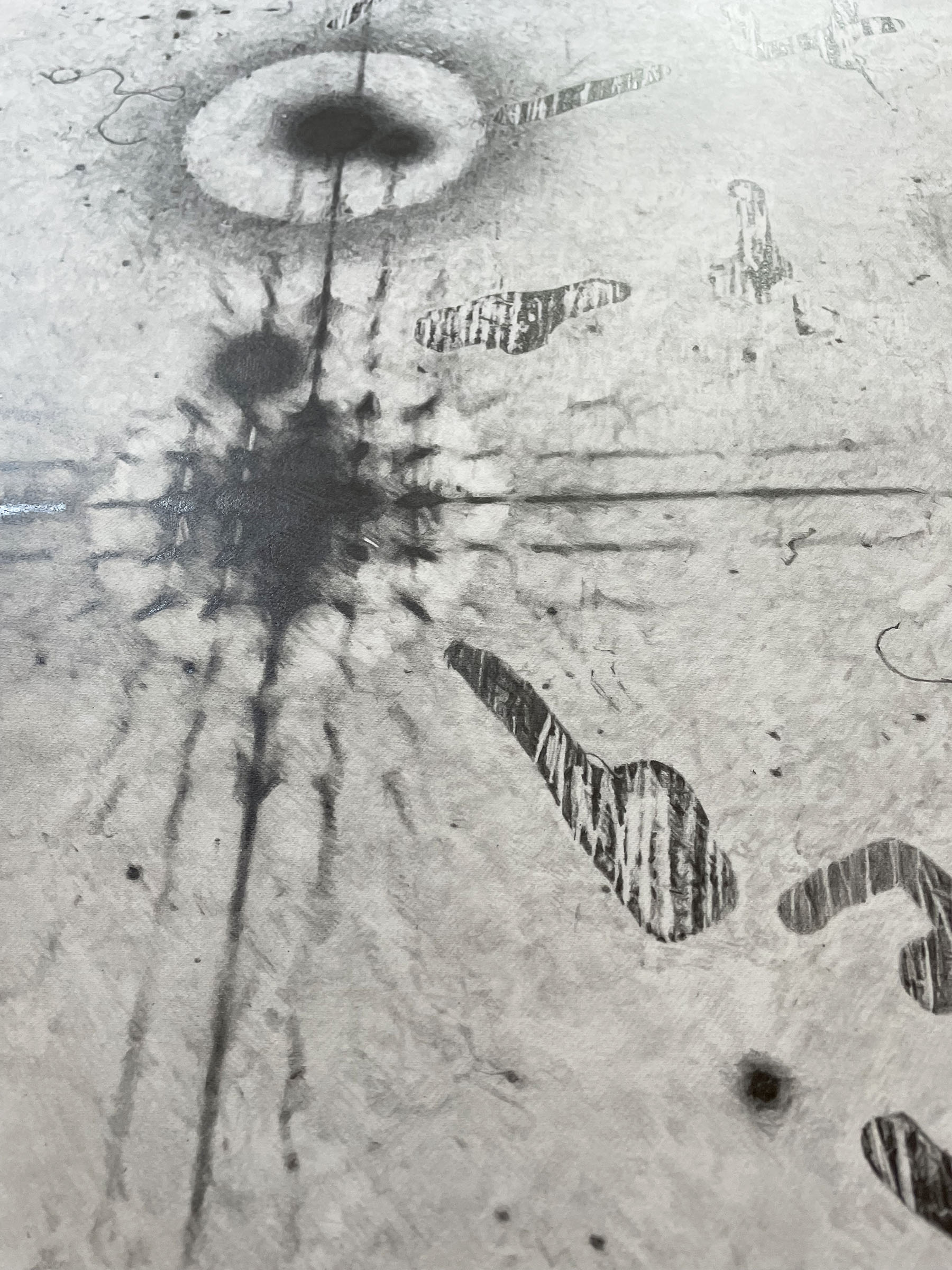

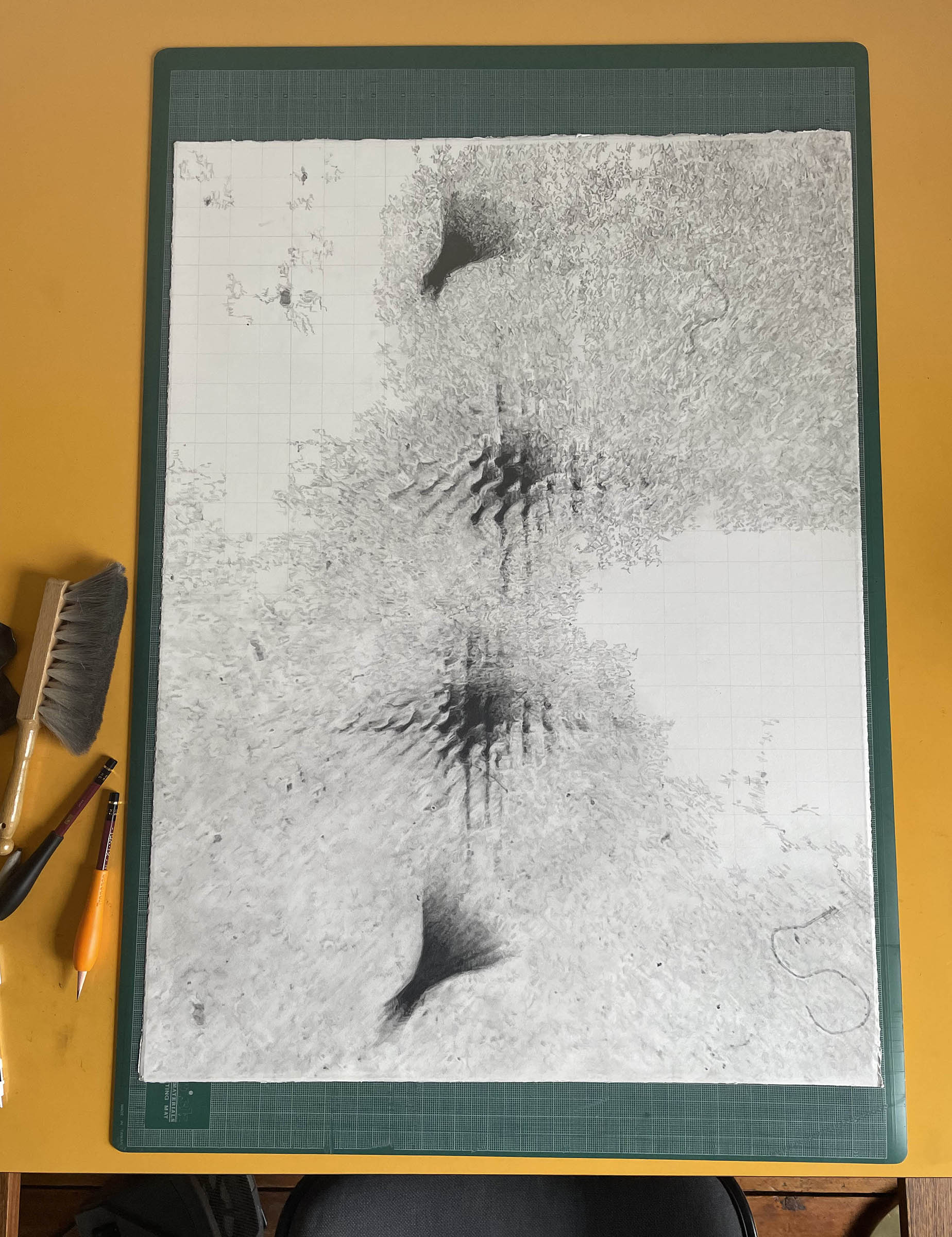

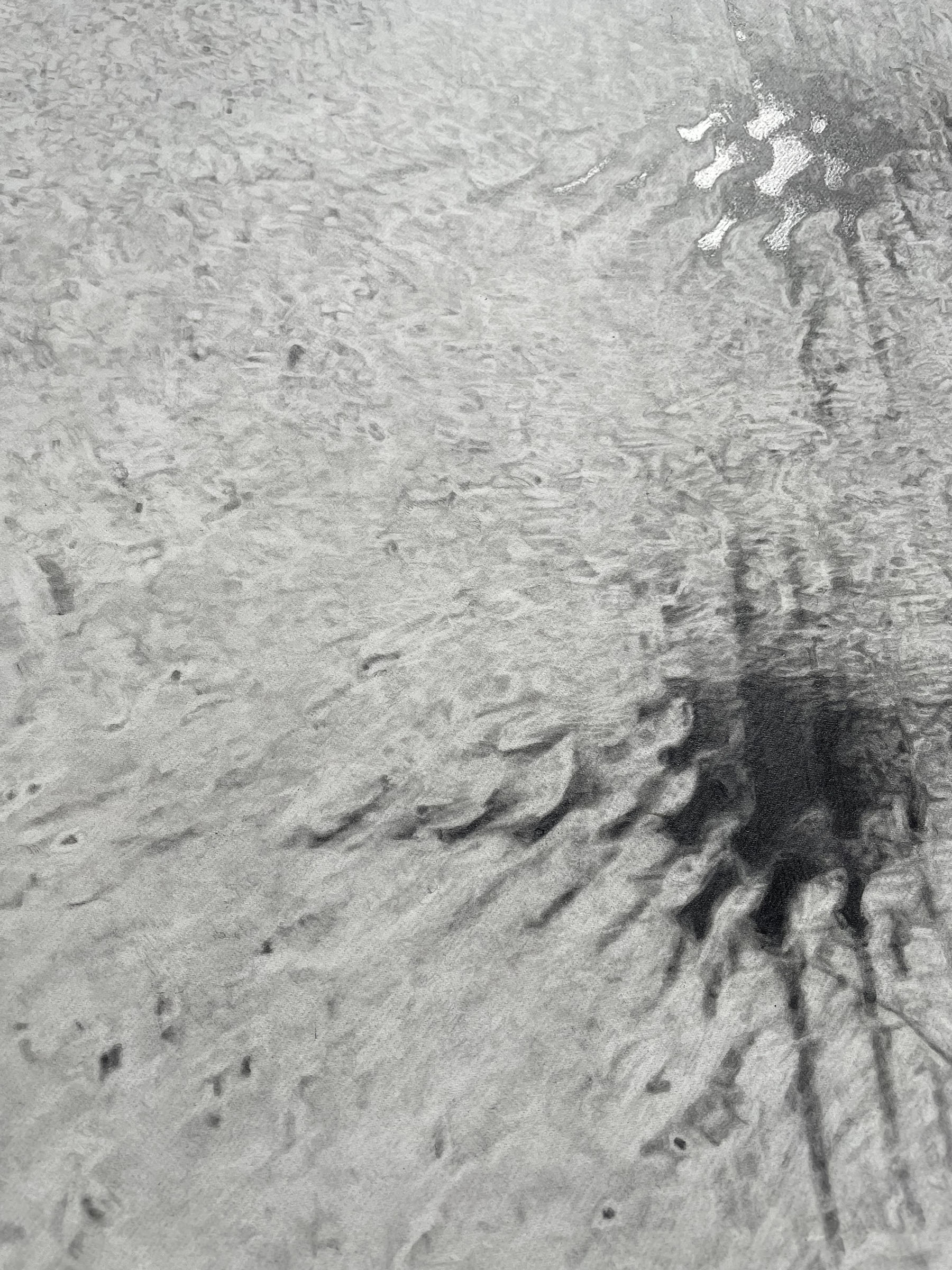

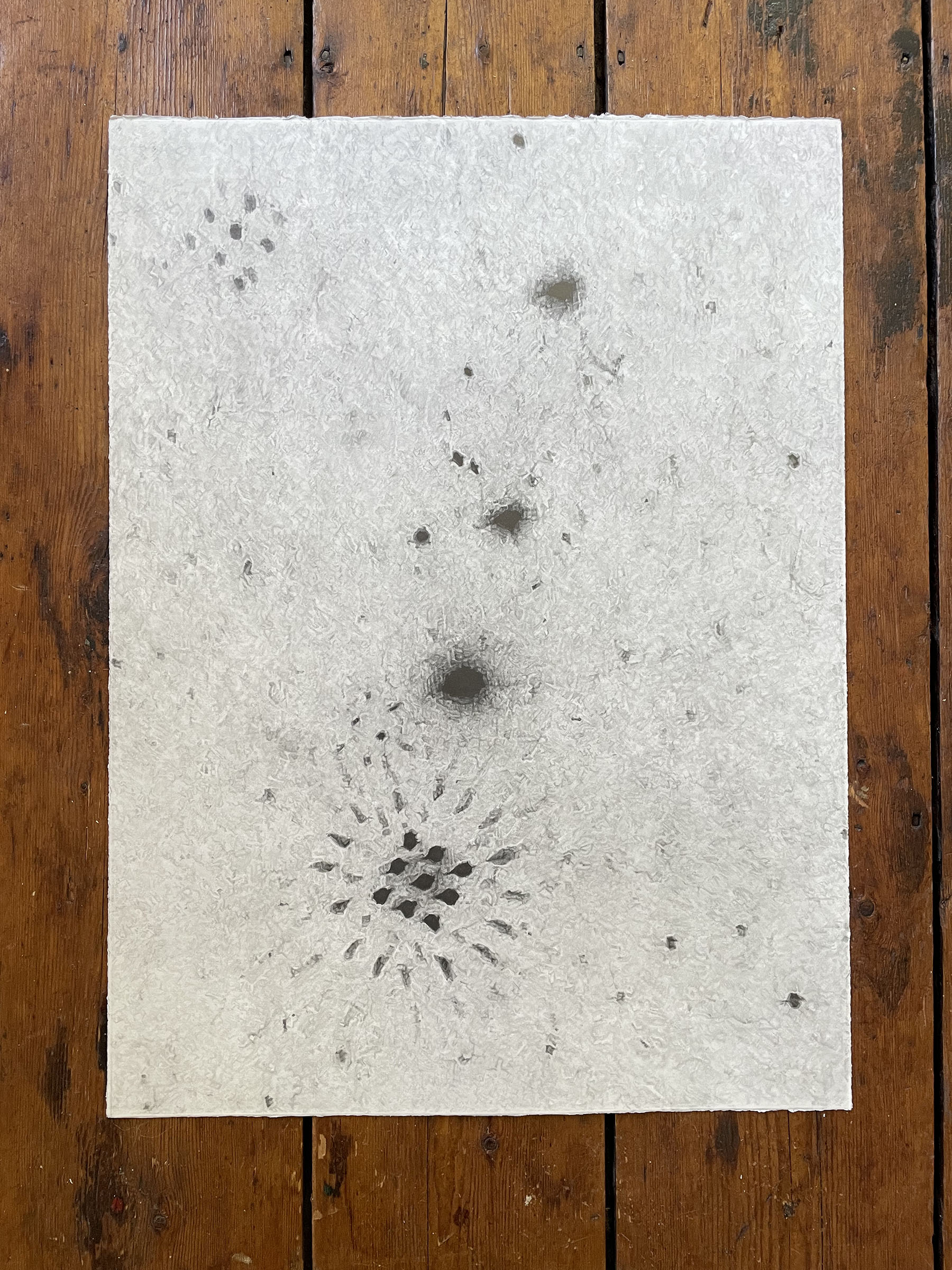

When delving into Leavitt’s methods, I realized how inventive she needed to be as she tried to discern how starlight, mediated by a new photographic technology developed in the late nineteenth century, translated onto glass. To standardize her North Polar Sequence—a sequence of ninety-six stars near the North Pole representing the widest possible range of brightness that once established could be used as a benchmark for all other stars in the sky—Leavitt directed the creation of multiple-exposure photographic glass plates. This allowed bright stars, which would otherwise be overexposed during the longer exposures required to capture fainter stars, to be in conversation with the dimmer stars in her sequence. Starlight was diffracted through the use of prisms, polarizers, diaphragms, and wire screens placed at the light-gathering end of the telescope to disperse or dampen the light of these bright stars before it contacted the photographic plate. With that light reduced by calculable amounts, Leavitt could then compare it to the known magnitudes of midrange stars shown in subsequent exposures taken without interference on the same plate.

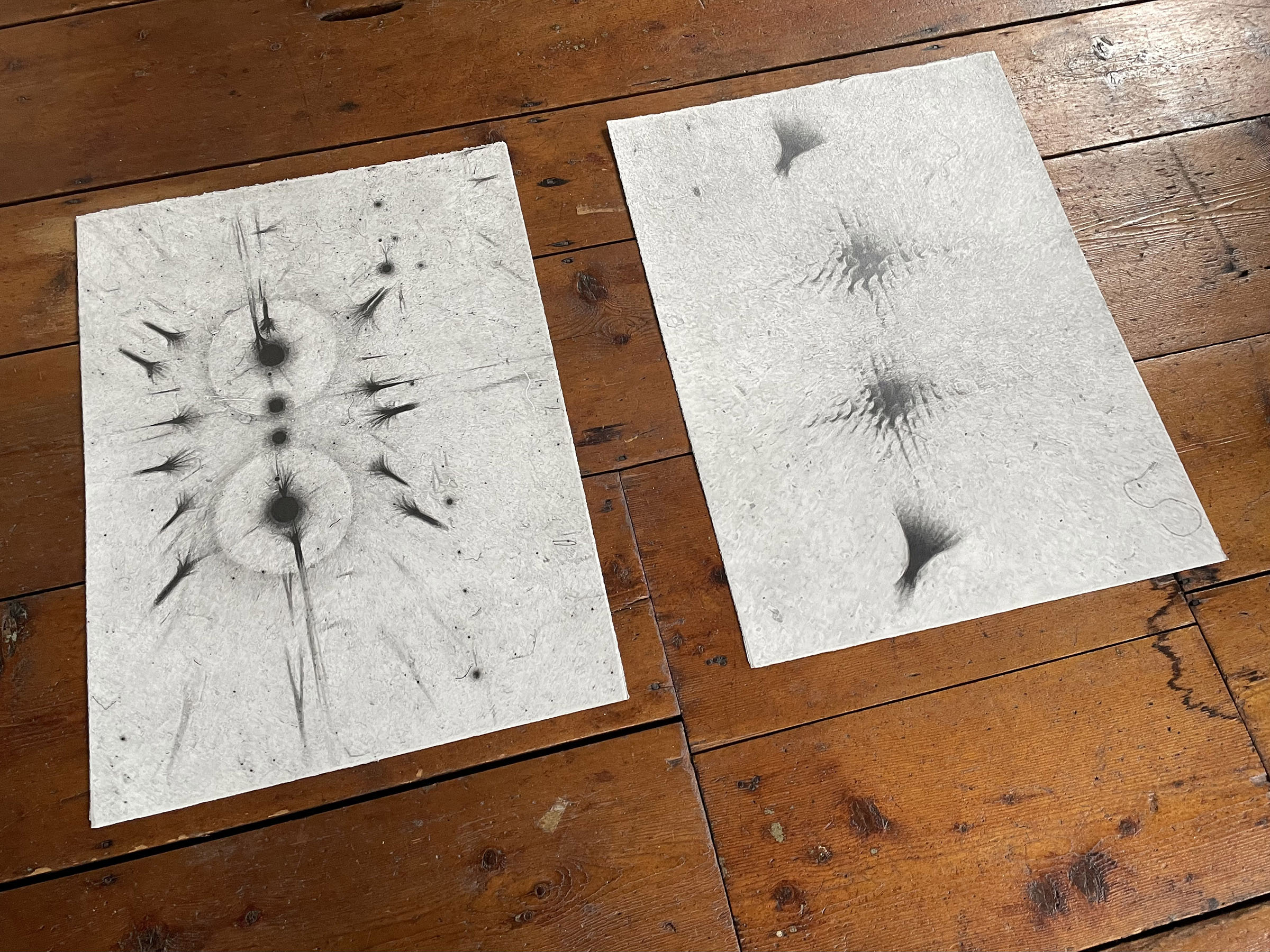

This series is based on magnified details of Polaris, the North Star, appearing on plates Leavitt notated in ink—plates that seem nondescript until close looking reveals the intricate and visually radical world she studied. Held in these drawings is Leavitt’s life spent looking, placed in conversation with my own time spent noticing. They remind us that the ordinary is always where the extraordinary lives.

Many thanks to Jennifer L. Roberts, who accompanied me on numerous research trips to the Harvard College Observatory’s Astronomical Photographic Glass Plate Collection and made the source photographs for these drawings using a macro lens. Roberts also contributed a guest essay to Attention Is Discovery and was a smart, intelligent, and wise first reader of the manuscript. I feel enormous gratitude for her collaboration in making this drawing series as well as the central role she has played as a part of my larger project on Henrietta Leavitt.

Many thanks as well to the people at the Harvard Plate Stacks for the generous access to these materials and their dedicated support.